by GreenMinute

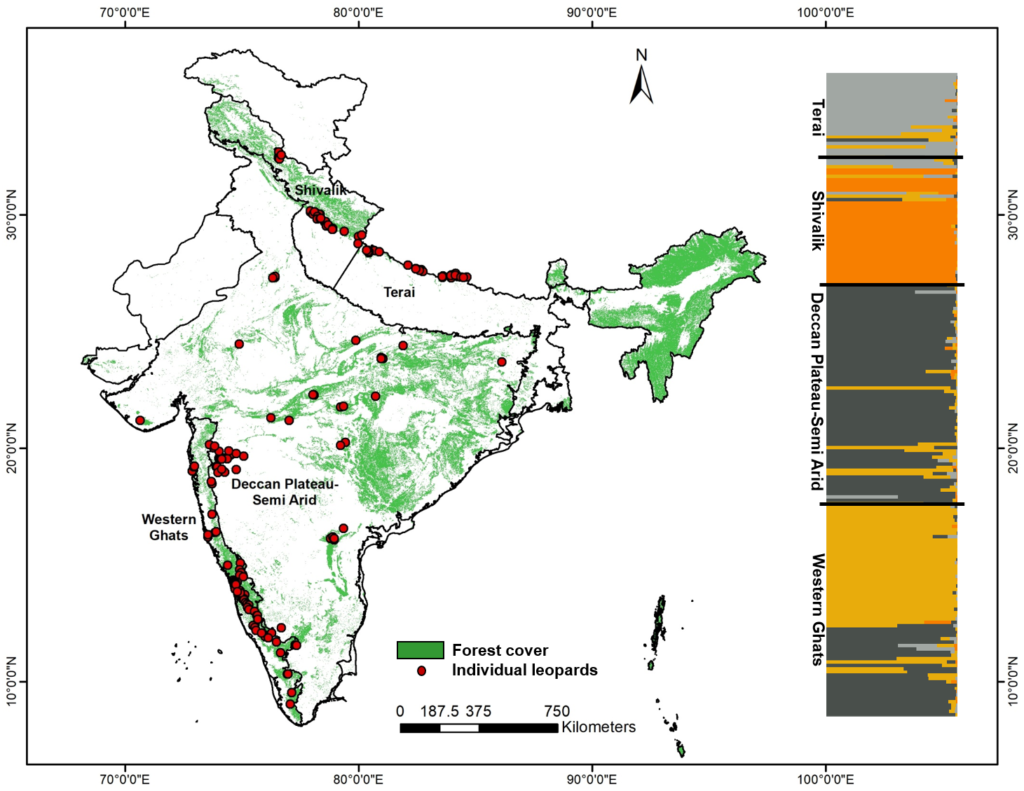

Scientific studies show a WHOPPING 70-90 per cent decline across four genetic sub-populations of Indian Leopards in the last two centuries. Subsequent analyses reveal distributions that suggest recent time of declines in all four populations of leopards. The north Indian subpopulations (Shivalik and Terai) and the Deccan Plateau-Semi Arid population showed the most recent decline that occurred about 120–125 years ago. However, the Western Ghats population indicated potential decline around 200 years ago.

In India, the latest ecological estimate of leopard population (2015) in the forested habitats of 14 tiger-inhabiting states is just 7910. As leopards do survive in highly human populated and modified areas, scientists say even this estimate is likely to be minimal and incomplete. However, lack of detailed, systematic field data makes it difficult to generate accurate population estimates as well as demographic patterns at landscape scales.

LARGE FELID SPECIES

Panthera pardus is probably the most widely distributed and highly adaptable large felid globally and still persisting in most of its historic range. The present study based on indirect genetic methods – scientists recommend detailed, landscape-level ecological studies on leopard populations as they are critical for future conservation efforts.

Among all the subspecies, the Indian leopard (P. p. fusca) retains the largest population size and range outside Africa. However, the reasons for their decline are recent increases in leopard-human conflict and poaching intensity due to large demand for leopard body parts in the illegal wildlife markets.

Added to this, large-scale landscape modification and fragmentation by humans during the last century coupled with poaching and conflict may have resulted in much recent loss of leopard populations across the country. Leopards also frequently occur outside protected areas, increasing their vulnerability to conflict with humans.

Unfortunately, there is still a paucity of information on their population and demography at the regional and global scales. Much of our knowledge on leopard ecology and demography in the Indian subcontinent come from location-specific studies, scientists say.

JOINT STUDIES

The studies were conducted by India’s premier government wildlife body, the Wildlife Institute of India and the Centre for Wildlife Studies (CWS, India). For this study, scientists used genetic data from leopards sampled across the Indian subcontinent to investigate population structure and patterns of demographic decline. They also investigated the demographic history of each identified sub-populations and compared the genetic decline analyses with countrywide local extinction probabilities.

The study has been published in the journal, PeerJ – Life and Environment by authors Supriya Bhatt Suvankar Biswas Dr Bivash Pandav and Dr Samrat Mondol (Wildlife Institute of India) and Dr Krithi K. Karanth (Centre for Wildlife Studies}.

FRESH SAMPLES

A total of 778 fresh large carnivore fecal samples were collected in the northern landscape. These samples were collected from both inside and outside protected areas from different parts of this landscape. Scientists say how they collected fecal samples and identified 56 unique individuals using a panel of 13 micro-satellite markers, and merged this data with already available 143 leopard individuals.

The study reveals population structure and recent decline in leopards. The results of the study also showed that coalescent simulations with microsatellite loci revealed a possibly human-induced 75–90 per cent leopard population decline between approximately 120–200 years ago.

“Our results are interesting and alarming – using two different methodological approaches. We have established that even the most adaptable big cats in India has experienced decline in population structure and distribution,” says Dr Krithi Karanth.

CONSERVATION ATTENTION

The study clearly indicates and suggests that leopards demand similar conservation attention like tigers in India. It also emphasizes the importance of similar work on wide-ranging and commonly perceived as locally abundant species, as it is possible that they may show population decline, especially in the context of the Anthropocene.

The study also deduces that population-specific estimates of genetic decline are in concurrence with ecological estimates of local extinction probabilities in these sub-populations.

STUDY HIGHLIGHTS

● Four genetic subpopulations of leopards found in India: the Western Ghats, Deccan Plateau-Semi Arid landscape, hill region of north India (Shivalik) and Terai region of north India

* While there was some amount of mixed signal across different genetic subpopulations, they were clearly separated as different groups

* Despite severe decline and small but significant population structure – leopards still retain high genetic variation in the Indian subcontinent

* The Deccan Plateau-Semi Arid, Shivalik and Terai subpopulations show 90%, 90% and 88% decline in population size, respectively while the Western Ghats show relatively less (75%) decline in population size

● Population specific estimates of genetic decline are in concordance with ecological estimates of local extinction probabilities

● Genetic clusters were formed due to restricted gene flow along major habitat type differences between these bio-geographic zones

==========================================

Comment here